A

Adummatu

The Syrian desert’s ancient metropolis Dumat al-Jandal (in the cuneiform sources in ancient Akkadian: Adummatu and the biblical Duma), was the oasis town among several pre-Islamic cities where people would travel to the annually held market fairs.

The dominant tribal group in the area, the Banu Kalb, practised slavery more than other tribes, so the Duma’s markets were known for slavery and prostitution. The oasis was a critical caravan station and a gate to Syria and Upper Mesopotamia, especially to Assur.

Today, Dumat al-Jandal (Al-Jawf or Al-Jouf) is an ancient city of ruins and the historical capital of the Al Jawf Province, North Western Saudi Arabia.

Akhet

Akhet is an Egyptian hieroglyph that represents the sun rising over a mountain. Akhet means the “horizon” or “the place in the sky where the sun rises”. It is also associated with creation and rebirth. The first season of the ancient Egyptian calendar was Akhet (appearance). It ran from mid-July to mid-November. (See: Ancient Egyptian Calendar).

Akitu Festival

The Akitu Festival began with a great procession through the Ishtar Gate towards the temple of Marduk.

The Babylonian New Year’s festival was celebrated to honour the supreme god Marduk, his crown prince Nabu and other gods in the first few days of the month of Nisan. Akitu was an important Babylonian temple located just outside the city, where the annual procession took place, and the temple’s doors opened only once at the beginning of every year.

The Akitu festival occurred in the spring, marking the rebirth of nature and the re-establishment of kingship by divine authority. It secured the life and destiny of the people for the coming year. The feast of Akitu represented a moment of joyous celebration for the Babylonian society and a particular moment for reflection upon their institutions, without which the New Year would begin inauspiciously.

Akkadian

The extinct language of Akkad, written in cuneiform, with two dialects, Assyrian and Babylonian, was widely used from about 3500 BC. It is the oldest Semitic language for which records exist. Akkad was in the northern part of ancient Babylonia, now central Iraq. The region was situated where the two rivers, the Tigris and the Euphrates, were closest to each other. Its northern border stretched beyond the modern cities of Baghdad and Al-Fallujah. The ancient populations of this area were mostly Semitic, and their speech was called Akkadian. Sumer, the southeastern partition of ancient Babylonia, lay south of Akkad, and the Sumerians, a non-Semitic people, settled there.

Akhmin / Akhmim

(See: City of Ipu)

Alashiya / Cyprus

Alashiya (Alasiya), in ancient times also known as the Kingdom of Alashiya, was a country in the Middle and Late Bronze Ages and was situated somewhere in the Eastern Mediterranean. It is referred to in several surviving texts and is now considered to be the ancient name of Cyprus or an area of Cyprus. It was a significant source of goods, especially copper, for ancient Egypt and other states in the Ancient Near East.

Amenhotep III.

Amenhotep III (c. 1386-1353 BCE) was the ninth king of the 18th Dynasty of Egypt. His other names found in ancient documents were Nebma’atre, Amenophis III, and Amana-Hatpa. All of this means that the god Amun is satisfied. He was the son of the pharaoh Thuthmosis IV and one of his lesser wives, Mutemwiya. Amenhotep III was the husband of Queen Tiye, the father of Akhenaten, and the grandfather of Tutankhamun and Ankhsenamun. Thuthmosis IV left his son an empire of immense size, wealth, and power. Amenhotep III inherited the throne of Egypt, the most powerful country in the ancient Middle East. Its treasury was full of gold, and its vassals bowed before the mighty rulers of the Two Lands (Egypt).

Amenhotep III was a master of diplomacy. Instead of wars, he periodically sent lavish gifts of gold to other nations. His generosity indebted them to Egypt, and they were inclined to bend to his wishes, which they often did. His treaties were well-established, and he enjoyed profitable relationships with the surrounding nations. Amenhotep III was a devoted supporter of the ancient Egyptian religion, and through this, he satisfied his greatest passion, the arts and building projects. During his long reign, Amenhotep III ordered the construction of over 250 buildings, temples, and sculptures, and it elevated Egypt to a level so splendid that everybody was in awe.

Part of Amenhotep III.’s diplomatic genius was that he had commemorated his deeds on numerous scarabs and sent them to the kings of neighbouring countries. This way, he constantly informed his allies and enemies about the strength and prosperity of Egypt and established his leading position in the middle eastern power play.

The only parts left of Amenhotep III’s mortuary temple are two of his statues, today known as the Colossi of Memnon. The immense size and intricacy of detail of the statues suggest that the temple - and his other building projects no longer existing - were equally or even more impressive.

His most significant contribution to Egyptian culture was maintaining peace and prosperity, enabling him to devote his time to the arts. He ruled Egypt for 38 years until his death with his First Wife, Queen Tiye. Amenhotep IV, later known as Akhenaten was his successor. The tomb of Pharaoh Amenhotep III (an outstanding monument) is located in the Western Valley of the Kings, KV 22.

Gigantic statues of Amenhotep III and his First Wife, Tiye - today in the Egyptian Museum of Cairo

Take a tour in the tomb of Amenhotep III.

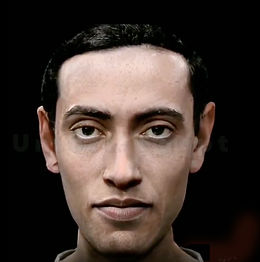

Amenhotep IV. / Akhenaton

Akhenaten (1353-1336 BCE) was the tenth pharaoh of the 18th Dynasty of ancient Egypt. He was born as the son of Amenhotep III and his First Wife Tiye. He was the husband of Queen Nefertiti, and father of both Tutankhamun (with a lesser wife named Kiya) and Tutankhamun’s wife Ankhsenamun (with Nefertiti).

His other names we found was ‘Akhenaton’ or ‘Ikhnaton’, which means ‘Successful for’ or ‘of Great use’ to the god Aten. Akhenaten chose this name after establishing a new cult dedicated to the Aten, the sun’s disk. Before this conversion, his name was Amenhotep IV (or Amenophis IV). He built a new capital called Akhetaten at Tell el-Amarna, 250 km (160 miles) south of Cairo.

In the first few years of his rule, Amenhotep IV has completely changed the religion, architecture, and art of ancient Egypt.

Akhenaten was finally buried in the Valley of the Kings. (KV55). It has long been speculated and disputed that the body found in this tomb was that of the famous king, Akhenaten. However, the results of genetic and other scientific tests published in February 2010 have confirmed that the person buried there was the son of Amenhotep III and the father of Tutankhamun.

The Royal Tomb at Tell el-Amarna (No. 26 in the Amarna rock-tomb sequence) lies in a narrow side valley leading off from the Royal Wadi at a distance of 6 km. Originally it was intended for Akhenaten, Princess Meketaten, and probably for Queen Tiye, and (in an unfinished extension) an additional person (maybe Nefertiti). Its basic design and proportions are similar to those of the royal tombs in the Valley of Kings at Thebes, except that there are additional burial chambers since it was intended for several persons.

Take a tour of the tomb of Akhenaten

Amenhotep Huy

Huy (Amenhotep called Huy) was the high steward in Memphis at the time of Amenhotep III. He also served as Unique Friend of the Lord of the Two Lands, the Royal Scribe and Chief Steward. His tomb is in Thebes - TT40.

Amenhotep, son of Hapu

Amenhotep, son of Hapu was a high official of the reign of Amenhotep III, who reigned between 1390–53 BCE. The pharaoh greatly honoured him during his lifetime, and more than 1,000 years later, during the Ptolemaic era, he became a deity.

Amenhotep rose through the ranks in the government, starting as a scribe of the recruits in the military office of Amenhotep III. In the Nile’s delta, Amenhotep was responsible for positioning soldiers at checkpoints by the river’s branches to control the foreign entries from the sea and the infiltration of Bedouin tribespeople by land. On one of his statues, he is called an army general.

Later he was placed in charge of all royal constructions and directed the building of Amenhotep III’s mortuary temple at Thebes (near modern Luxor), the temple of Soleb in Nubia (modern Sudan), and the transport of building materials and erection of other works. We found inscriptions on two statues from Thebes noting that he was also a negotiator in the Amon temple and that he managed the celebration of one of Amenhotep III’s Heb-Sed festivals (see Heb Festival). The pharaoh honoured him by adorning Athribis, the general’s native city. An inscription on a limestone stela records how Amenhotep, son of Hapu, was allowed to build a mortuary temple right next to the temple of Amenhotep III. It was a unique honour for a nonroyal person in Egypt.

Some of his titles: Hereditary prince, count, sole companion, fan-bearer on the king’s right hand, chief of the king’s works, even all the great monuments which are brought, of every excellent costly stone; steward of the King’s-daughter of the king’s-wife, Sitamen, who liveth. His other titles were the overseer of the cattle of Amon in the South and North, chief of the prophets of Horus, lord of Athribis, and festival leader of Amon.

Some records suggest that Amenhotep was buried near Thebes, while others say a tomb was built for him in Qurnet El Murnai. Although we found parts of his sarcophagus, the exact burial location is unknown.

Some of his statues are around the world:

Statue at the Luxor Museum, Egypt.

Statue, Granite, from the Temple of Amun-Re, Karnak. New Kingdom, 18th Dynasty Egyptian Museum, Cairo. JE 44861

Statue fragment with inscriptions

British Museum EA 103

Amenmose

Amenmose and his wife, Taka

Torino Museum -painted limestone

Amenmose - Tomb painting - Metropolitan Museum, New York

Amenmose was the ‘Steward in the Southern City’ (the southern city for them meant Thebes) at the time of Amenhotep III. His tomb holds many important court and domestic scenes and some detailed portraits of Amenhotep III. and Thutmosis III.

Based on his tomb’s decorations the Egyptologists assume that Amenmose started his career under king Thutmose III. and served until his death in the middle of Amenhotep III's reign.

Based on his tomb’s decorations, Egyptologists assume that Amenmose started his career under king Thutmose III. and served until he died in the middle of Amenhotep III.’s reign.

In the painting, it would appear that Amenmose looked back to his service under Tuthmosis III. however, he gives more importance to Amenhotep III., the reigning king, when his tomb was made. His son possibly inherited his titles after Amenmose’s death because he appears beside his father in many scenes of the grave. Most of the original colors are intact in the tomb, but he likely gave his titles to him after his death.

The tomb is carved into the limestone of the mountain’s steep slope, with a courtyard and two rooms. Although about half of the tomb decoration is destroyed, it is still one of the most beautiful tombs in the nobles’ cemetery.

(Theban Necropolis: TT89)

Amun

Amun statuette

Metropolitan Museum of Art

New York

Amun wearing his two-feather crown on the White Chapel of Senusret I at Karnak

Amun (also Amon, Ammon, Amen) was the ancient Egyptian god of the sun and air. His name means “The hidden one,” “Invisible”, and “Mysterious of form”. Amun was the most important god of ancient Egypt. Starting from the New Kingdom (1570-1069 BCE), Amun’s main worshipping city was Thebes. The Egyptians considered him the ‘Lord of All’, encompassing every aspect of creation.

He usually appeared on paintings and statues as a man with a long beard wearing a headdress with a double plume. In his role as Amun-Min, he was depicted as a ram-headed man or simply a ram, symbolizing fertility in the New Kingdom.

The ancient Egyptian people considered Amun as the pharaoh’s father and protector. The Amun priests were among the richest in Egypt because they controlled vast lands and resources. The women closely involved with the Amun cult had immense power in society.

Statue of the God’s Wife of Amun and Divine Adoratrice of Amun

Gold-plated silver figure of Amun-Ra

British Museum

Anen

Statue of Anen - Museum of Turin

The brother of Queen Tiye, Anen was the brother-in-law of Amenhotep III, a maternal uncle to Akhenaten and a maternal great-uncle to Tutankhamun.

Anen probably served in the military before joining the priesthood and earned several honourable titles, including 'Guardian of the Palanquin', 'Second of the Four Prophets of Amun' and 'Greatest of Seers'. Beyond his high spiritual standing, Anen also came from a famous regal line. During his career, he became Chancellor of Lower Egypt, Second Prophet of Amun, sem-priest of Iunu (today Heliopolis), and Divine Father under the reign of Amenhotep III.

It is unclear when Anen rose to importance, but his priestly titles show that he found great favour at court.

His tomb’s paintings mention his wife, son and four daughters, but none of their names have been preserved.

Anen - wooden shabti

Rijksmuseum

Anen's tomb (TT120) is at the highest point of Luxor’s West Bank’s royal necropolis hill.

Scene from Anen’s tomb showing Amenhotep III. and Queen Tiye seated on thrones in a kiosk. Only the lower portion of the image still remains.

Ancient Egyptian calendar

The ancient Egyptian calendar started with Akhet (appearance) as the first season of the year. It ran from mid-July to mid-November. Akhet was the season in which the inundation occurred, so it was dedicated to the god Hapi (See Hapi). The people hoped the god would ensure the flood was neither too low (which could have resulted with a poor harvest) nor too high (that could have destroyed their mud-brick houses and paths near the Nile).

The ancient Egyptians associated the inundation with the star Sirius. The star reappeared (after a seventy-day absence) at the new year, heralding the flood.

While the inundation was a quiet time for farmers, because the water submerged their fields, they could take on other jobs for the state to earn tax relief (tax was a proportion of the food they produced. For example, farmers could help construct monuments such as the pyramids during the Old Kingdom in return for living expenses and a tax rebate.

Wep Renpet (the ancient Egyptian New Year’s Day) The ancient Egyptians celebrated this day as the first day of their civic calendar. The festival marked the New Year and celebrated rejuvenation and rebirth.

Ancient calendar with the Egyptian zodiac Louvre, Paris

Ancient Egyptian calendar - Karnak, Luxor

Aniusi

Fragment of a standing female figure (priestess) with clasped hands Mesopotamia,

Musée du Louvre, Paris

Aniusi was a high priestess of the Babylonian goddess Nanshe (cca. 1300 BC.). As she served the goddess Nanshe, Aniusi’s role was to help people understand their problems better, interpret their dreams and visions, and to protect the orphans.

Nanshe was also the goddess of fresh water and its flora and fauna, so the temple where Aniusi lived was built on an island in the marshlands of the river, and it was entirely made of reed.

(See Nanshe)

Fragment of a vessel with frontal image of a priestess in Mesopotamia.

Berlin-Vorderasiatisches Museum.

Ankh (or Anakh)

Ankh Shaped Wooden Mirror Box

from the tomb of Tutankhamun

Isis gives the ankh as the symbol of eternal life to Nefertari,

painting in the tomb of Nefertari

The Ankh is the most common symbol in ancient Egyptian history, and we find it most everywhere. The meaning of this symbol is “the key of life” or the “cross of life”. Historians are still debating its origins, and archaeologists found its earliest traces from the Early Dynastic Period (c. 3150 - 2613 BCE). The Ankh looks like a cross with a loop at the top, sometimes joined with the Djed and Was symbols. Many ancient Egyptian gods carried it in this form in tomb paintings and inscriptions, and the people often wore it as a powerful amulet. It is also a hieroglyph for “Life” or “Breath of life” (‘nh = Ankh). The Egyptians believed that life on earth was only part of eternal life. The Ankh symbolizes both mortal existence and the afterlife.

The ancient Egyptian religion associated the Ankh with the mirror, and it wasn’t by any chance. They believed the afterlife was a mirror image of life on earth. Therefore, the mirrors for them contained magical properties. Every household in ancient Egypt would burn oil lamps during the night. They believed that the tiny flames reflected the stars of the sky. This way, they created a mirror image of the heavens on earth during the Festival of the Lanterns dedicated to the goddess Neith. The people believed that the tiny flames helped to part the veil between the living and the dead. They hoped one could speak to those friends and loved ones who had passed on to paradise in the Field of Reeds. The priests and fortunetellers often used mirrors from the Middle Kingdom onwards for divination.

(See Neith and Field of Reeds)

Anubis

Anubis with a jackal’s head and man’s body

Metropolitan Museum, New York

.jpeg)

Anubis (Inpew, Yinepu, Anpu) was the ancient Egyptian god of graveyards and embalming. The Egyptians paid respect to their dead just like the people did in any other part of the world. They mummified the deceased with the help of Anubis and conducted elaborate ceremonies to help them to pass smoothly into the Afterlife. Anubis was the deity who played an essential role in this journey in the form of a black-headed jackal.

The ancient Egyptians called their country ‘The black land of Khemet’ because the color black for them represented the fertile soil of the Nile needed to grow yearly crops. In addition, they believed that black symbolized good fortune and rebirth.

The Egyptians respected the goddess Ma’at (who ensured order, peace, and balance in the universe), so death was as important as life for them. Anubis was a significant part of the transition from death back to life again.

Anubis in the tomb of a son of Ramses III in the Valley of the Queens (QV44)

Anubis by the embalming ritual

Anubis in jackal form

Metropolitan Museum, New York

Anubis - papyrus Nauny, a Chantress of the god Amun-Re

Apep

Apep (Apepi, Rerek and later in Greek, Apophis) was an ancient Egyptian demon of chaos in the form of a gigantic serpent and the eternal enemy of the sun god, Ra. Although many serpents symbolized divinity and royalty, Apep threatened the world and represented evil.

In the ancient Egyptian creation myth, when Ra emerged from the dark waters of nothingness, he fought Apep, a demonic serpentine creature of chaos and destruction dwelling in the darkness for the first time. Apep was against the rising light, and then the world Ra created. The sun god subdued the serpent, and Apep was not allowed in the mortal world, but every night Apep attacked Re in his divine bark at a particular hour as the sun travelled through the underworld or under the horizon. Re’s children, the other gods, have defended Ra, but Apep hypnotized the sun god and his followers, except for Seth, who was in the front of the bark. Seth then struck and slew him with a spear, but the next night Apep (who could have never been permanently destroyed), attacked Re again. The Egyptians believed the king could help maintain the world’s order, and by performing the necessary rituals, he would assist Re against Apep.

Apep relief in Edfu

Bastet protecting Ra during the night by fighting Apep,

Papyrus of Hunefer,

Re in his solar boat battling Apep

_%20Egyptian_%20Third%20Intermediate%20Period%2C%20Dyn.jpeg)

Apep in the underworld

Coffin Base of a Priestly Official (detail). Third Intermediate Period, Dynasty 21, cca.1076-944 BC.

Wood, painted gesso. Charlotte Lichirie Collection of Egyptian Art.

Api Bull

Api (or Apis) was ancient Egypt’s most important and highly regarded bull deity. His original name in ancient Egyptian was Api, Hapi, or Hep.

The archaeologists found evidence of the worship of the Apis bull from the earliest times of ancient Egyptian history. During the First Dynasty (c. 3150 - c. 2890 BCE), we found evidence that they organized rituals known as ‘The Running of Apis’. It seems that Apis may have been the first animal associated with divinity and eternity. The bull originally was a fertility god, then the herald of the god Ptah. Later the people considered him the god Ptah incarnate.

Api bull

The Api bull is depicted throughout Egypt’s history as a striding bull with a solar disc and uraeus (the sacred serpent symbolizing the king’s power) between its horns.

The ancient Egyptians carefully searched and then selected the Apis bull. It had to be black with a white triangular marking on its forehead and another white marking on its back in the shape of a hawk’s or vulture’s wings. In addition, it had to bear a white crescent on its side, a separation of the hairs at the end of its tail (known as the “double hairs”). Most importantly, the bull had to have a lump under its tongue shaped like a scarab. If the priests found a bull with all these characteristics, they instantly recognized it as Apis. But so many characteristic elements are rare to manifest altogether, so a white marking in the form of a triangle on the forehead and the scarab-shaped lump under the tongue was often enough to choose the bull.

Once the priests chose the bull, it was brought to Memphis and housed in the temple precinct with his mother. People would travel to the city from all over the country to worship the animals.

Api bull The sacred Apis bull shown on a Twenty-first dynasty Egyptian coffin

The burial place of the Api (sacred) bulls is at the Serapeum at Saqqara. It is located northwest of the Pyramid of Djoser at Saqqara near Memphis in Lower Egypt.

Apis Stele to Apis. Reign of Psametik I. Louvre Museum, Paris

Api bull mummy

Serapheum - Saqqara

Aqhat

Aqhat was a mercenary soldier in the troop of Nebamun. He belonged to a social group called Habiru (Hapiru), meaning “those who cross from the other side, nomads”. Habiru is a term used in 2nd-millennium BC texts throughout the Fertile Crescent for people described as rebels, outlaws, raiders, mercenaries, bowmen, servants, slaves, and labourers.

A temple relief depicting Medjay mercenary archers.

Arzawa

Arzawa was an ancient kingdom of western or southwestern Anatolia (historians still dispute its exact location). Although Arzawa was a rival of the Hittite kingdom for long periods, it was occasionally conquered and made a vassal by some of the more powerful Hittite kings, such as Labarnas I (c. 1680–c. 1650 BC). During the period of Hittite decline after the end of the Old Kingdom (c. 1500 BC), Arzawa’s power and prominence reached its peak, and its king, Tarkhundaradu, corresponded with Amenhotep III of Egypt in the 14th century BC.

Ashtan

Ashtan is a sinister personality with unclear origins. The anagram of his name (Shatan) exists in myths and religions even today. He existed already along the primordial gods and has no age. He is tirelessly searching for the “secret" the other gods left on Earth and pursuing anything and anybody to reach it. Evil, ruthless and has powers that are unexplainable to humans.

Asim

Asim was an old caretaker of the lions of the Sekhmet temple in Men-Nefer.

Astarte

Astarte (original Babylonian name: Ishtar) was one of the most important goddesses in the Northwestern Semitic regions. She was closely related in name, origins, and functions to the goddess Ishtar in Mesopotamian texts.

Astarte represented the fertility of crops and cattle, sexuality, and war. Her sacred animals were the lion, the horse, the sphinx, and the dove. Her symbol was also a star within a circle indicating the planet, Venus. Pictorial representations often show her naked. She has also been identified as the goddess embodying the evening star.

The ancient Egyptians adopted Astarte from the Mesopotamian religions (Ishtar), just like the Greeks did later, with the name Aphrodite and the Romas, as Venere.

Aten Tjehen

One of the names of the Royal Barque of Amenhotep III., it means “The Dazzling Sun Disk”. Amenhotep III also wore this title to show his godlike origins.

Atun / Aten

The word Aten (Atun) appears as early as the Old Kingdom, meaning “Disc”. In the ancient Egyptian language, it referred to anything flat and circular. The Egyptians called the sun the “Disc of the day”, where they thought their sun god Ra resided.

Atun (also spelled as Aten) was a sun god in ancient Egyptian religion. On the imageries, he appears as the solar disk emitting rays ending in human hands. The people extensively worshipped Aten as a god in the reign of Amenhotep III, but Atun’s worship briefly became the state religion during the reign of his son.

The pharaoh Akhenaton (reigned 1353–36 BCE) declared the supremacy of Aton, with the startling innovation that the sun god was to be the only god. Akhenaton wanted to remove himself from the preeminent cult of Amon-Re at Thebes, so he built a new capital (now Tell el-Amarna) as the center for Aton’s worship.

(See Ra)

Atum

Atum, Aton, Ra, Horakhty and Khepri made up the different aspects of the sun, whereas Atum was associated with the setting sun, which travelled through the underworld every night.

The archaeologists found Atum’s earliest records in the Pyramid Texts (inscribed in the tombs of the pharaohs from the fifth and sixth dynasty) and the Coffin Texts (in the tombs of nobles of the same period).

As in many creation stories around the world’s ancient religions, also by the Egyptians in the beginning, there was the endless water of nothing (Nun). Then a small piece of earth rose from Nun, where Atum created himself. Shu (air) and Tefnut (moisture) were born from his spit. Atum’s two offspring wandered away from him, and they got lost in the Nun, so Atum sent his “Eye” to look for them. This epithet was the precursor to the so-called “Eye of Ra", a label many deities wore at different times.

(See Tefnut)

At a certain point in the creation story, Atum became tired and wanted a resting place. He kissed his daughter, Tefnut, and created the first piece of land (Iunu) to rise from the Nun. Shu and Tefnut had two children, Geb (the earth) and Nut (the sky), who then became the parents of Osiris, Isis, Set, Nephthys and Horus, the elder. (See Benben)

While all the gods descended from Shu and Tefnut, Atum was considered to be the father of the pharaohs, so many pharaohs used the title “Son of Atum”. We can discover evidence that the ancient Egyptians believed in Atum’s close relationship with the king in many cultic rituals and the coronation rites.

Ay

Kheperkheperura-Ay was the last pharaoh of the 18th dynasty. He reigned briefly (only 3-4 years - 1346-1343 BC) and succeeded the young Tutankhamun. The reign of Ay closed the era called “The Amarna period”, during which Akhenaton, “The heretic”, tried to change the thousand-year-old religious system of the country. After Akhenaton’s death, the successive pharaohs returned to their old religion.

The period after Akhenaton remained confused. It was necessary to wait for the accession to the throne of the legitimate heir, Tutankhamun, to clear the religious order and reestablish the priesthood’s power stability.

According to some theories, Ay was the brother of queen Tiye, which connected him to the royal family but not by blood. Despite the absence of his biological connection with the reigning family and the fact that he organized the return to orthodoxy, people bound Ay to the Amarna period. He was included in the ‘damnatio memoriae’ (“condemnation of memory”), which erased the official history between the reigns of Amenhotep III and Horemheb, who succeeded him.

As Tutankhamun died young and unexpectedly without time to prepare a tomb for himself, the priests buried him in the grave prepared for Ay in the East Valley of the Kings (KV62). However, when Ay died, the unused tomb of Tutankhamun was ready, so he was buried there in the West Valley of the Kings (WV23).

Aya

In Akkadian mythology, Aya was the mother goddess, the consort of the sun god Shamash. She was the goddess of the Universe in Babylon.

(See Akkadian)

Her marriage with the sun god gave her powers upon the sunlight, especially regarding the sunrise since “Aya” is the Akkadian word for “dawn”.

Possibly much earlier than the Neo-Babylonian period, Shamash and Aya were connected with the so-called Hasadu, in rough translation, the "Sacred Marriage".

Aya was quite a popular personal name associated with female slaves working for the nadītu, the sacred priestess from the temples.

Aya is identified in a royal seal next to Šamaš, both showing human shapes. The goddess wears the woollen skirt, so common in Mesopotamian iconography. She also wears a mantle and her hair up with what could be a tiara, a diadem or some other hair ornament. Generally, Aya’s aspect is the one of a noble, high-class lady, highlighting her role as the spouse of the Sun.